|

Links Within This Section: |

|

Pinned Beater Loom Research |

|

| The British Link | |

Fly-Shuttle Loom Find Revives Research Hopes |

|

| Links to Other Website Sections |

|

| *For Photographs Click on Bold Underlined Words in Text* | |

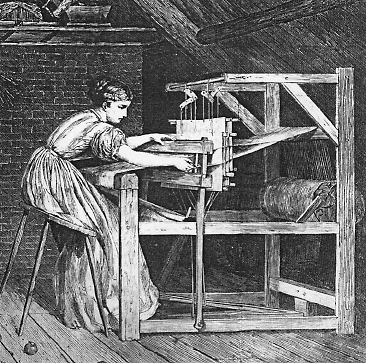

I began researching the evolution of weaving and the history of loom development when I acquired, and restored, my great grandmother's old rocker beater loom as part of a master's thesis project.

I started out by reviewing the standard loom literature but was unable to find any reference to the rocker beater element. So, in an all-out effort to locate information on this component, I began contacting museums, loom authorities, and weaving guilds in the United States and abroad. I also began locating additional looms - which turned out to be a less difficult task than locating specific information on the style.

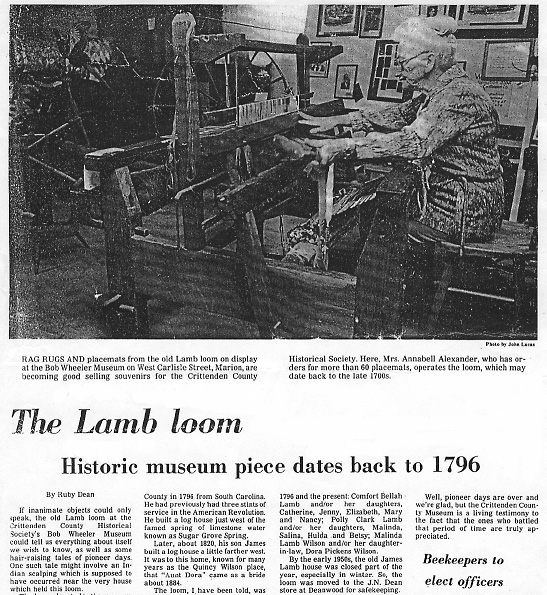

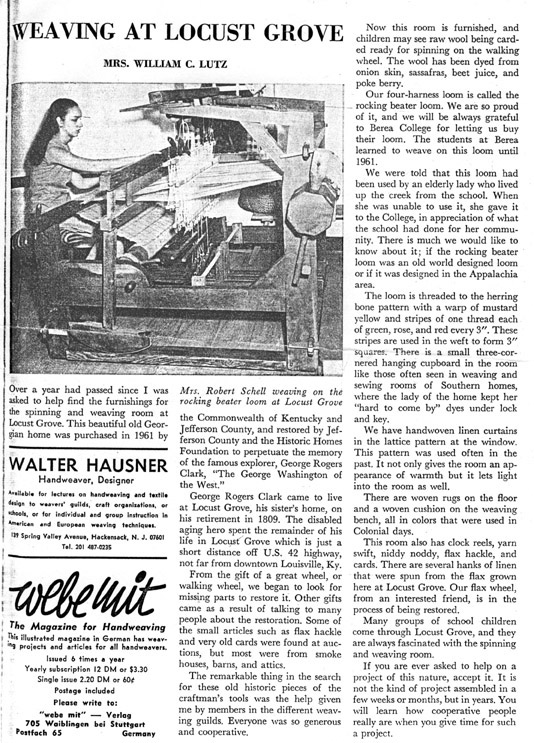

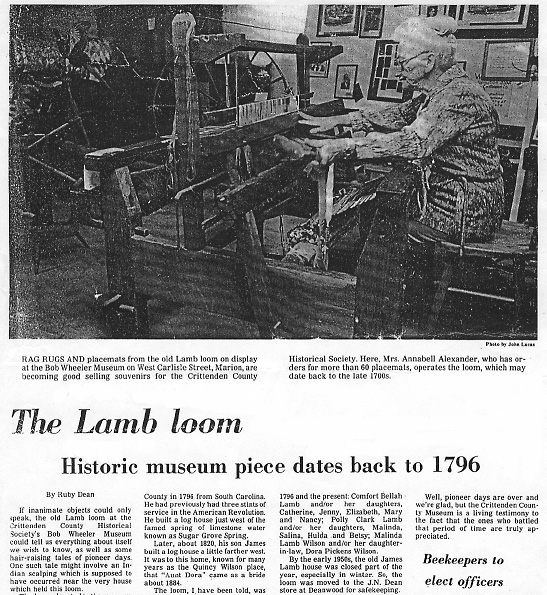

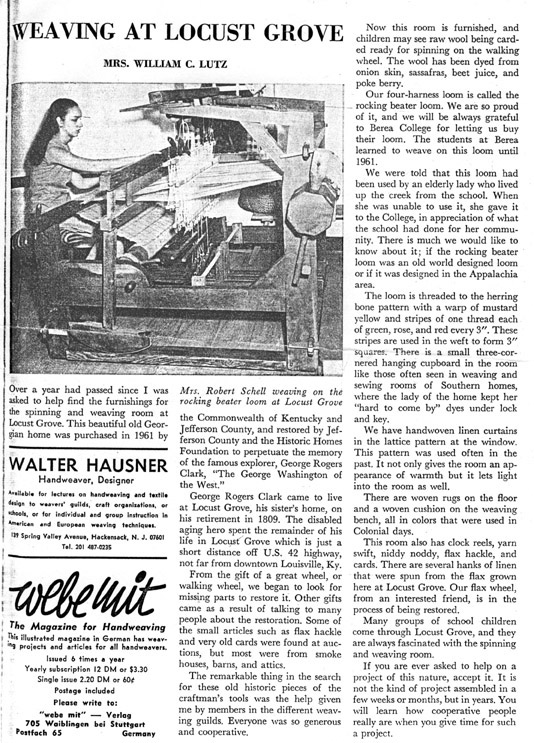

I found numerous rocker beater looms, but only three published references about them. The first reference was a newspaper article written by my great aunt concerning another old loom in our family, "The Lamb loom: Historic museum piece dates back to 1796," published in the Crittenden County Kentucky Press (October 11, 1979, p. 8). The second reference I found was in a 1968 magazine article, "Weaving at Locust Grove" from Handweaver and Craftsman, 19, p. 31, with a picture and the following statement "there is much we would like to know about it (the loom); if the rocking beater was an old world design or if it was designed in the Appalachian area."

The third reference was a written description of a rocker beater loom in Allen Eaton's Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands, "The old looms were of two general types: those in which all the apparatus was swung in the upper part of the frame; and a much less frequently used type called the cradle-rock loom, in which part of the mechanism, including the beating apparatus operated on a rocker below" (1973, p. 101).

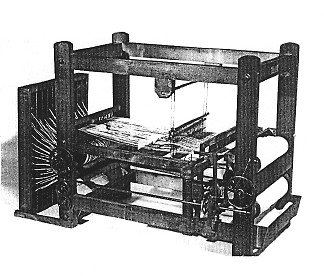

The rocker beater loom is classified as a standing beater loom (as opposed to a hanging beater loom). Therefore, the development of the standing beater loom has also been part of my research. The loom most widely recognized as the first to include a standing beater, is Edmund Cartwright's power loom, patented by the British government in 1787. With the Industrial Revolution in full swing there had been, for years, a huge demand for loom designs which could work within the factory system (with many machines running simultaneously, and continuously, off a single source of power). Efforts to combine automatic power and the hanging beater had failed, because the awkward motions of the beater led to frequent warp breakages which closed down the entire system until individual threads were retied. Despite this problem, it was hard to envision a weaving process which excluded the hanging beater. The major breakthrough came when Cartwright, a non-weaver who had never seen a loom at work, became fascinated by the motions of an automaton figure playing chess in a London exhibition and applied the same principles to his own perception of the weaving process. The result was "a truly creative power loom" which he patented in 1785. Only then did he "condescend to see how other people wove" and was surprised to see "their easy modes of operation" compared with his own. Making use of what he learned, he then went on to produce several additional looms. His final loom, patented in 1787 (see model pictured below), brought him both fame and fortune.

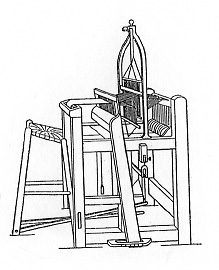

In doing extensive research, however, I eventually found a reference to a standing beater loom which predates Cartwright's loom. A small handloom with a unique, "inverted," beater that won a Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce (RSA London) award for British inventor, John Almond, in 1771 (years before the Cartwright inventions). John Almond's loom is documented in The History and Principles of Weaving, by Hand and by Power, an out-of-print resource by Alfred Barlow (1878, pp. 224, 245); this was an important find for me, not only because of the loom's resemblance to many of the rocker beater looms in my study, but as documented proof the standing beater existed prior to powerloom technology.

Eric Broudy's Book Of Looms provides an additional reference, a picture of an early American version of the standing beater loom, along with this explanation: "sometime during the nineteenth century … the beater, which had swung from an over-head bar since medieval times was flipped upside down and pivoted on pins in the lower side bars … called the 'little rocking loom' in the Southern Highlands of Appalachia, that became the prototype for the contemporary treadle loom used by most handweavers today." (Broudy 1979, pp. 160,161).

'Little Rocking Loom'

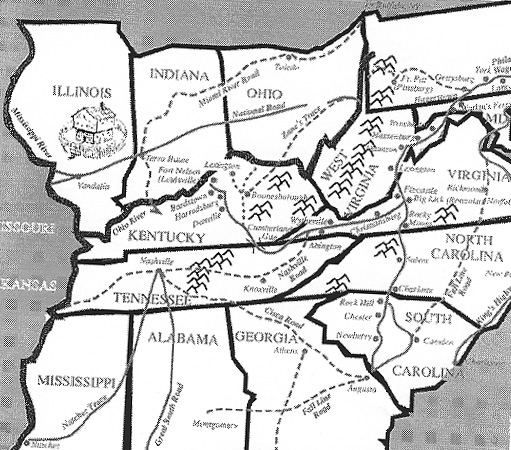

My search for additional rocker beater looms was, and continues to be, quite successful (60 as of April, 2014). I started photographing and documenting the looms myself, and found that most loom owners have little background information on their looms, or on the style. The owners with the most information are those whose looms have remained within the original family -- and they usually have two things in common. First, their ancestors were either among the early settlers in southwestern Virginia, or they had been from points east (typically Virginia or North Carolina) and had passed through the area on their way to new states and territories that were opening to settlement during the late 1700s and early 1800s. Second, they had usually been told by a "loom expert" that the standing beater on their loom dated its construction to the late 1800s -- and that any oral history passed down with the loom (concerning earlier construction and usage) simply could not be accurate.

I, too, ran into this argument early in my research, but knowing the history of the two looms in my own family gave me the confidence to question this position. In doing so, I learned no actual research had been done with regard to the appearance of standing beaters on handlooms, and the late 1800s date represented a conservative estimate, at best. The discovery of John Almond's 1771 handloom negated that argument completely and provided a model so closely resembling some of the rocker beater looms that it gave rise to the theory that the Almond loom may have actually inspired the style. There were, however, major differences between Almond's loom and the American rocker beater looms -- the most important being that instead of having rockers, the legs of Almond's beater were simply pinned to the base of the loom frame.

I examined the western migration patterns in reverse, looking for "hot beds" of looms in eastern locations (i.e. North Carolina, Virginia, Pennsylvania), to see if a geographic point of origin for the style might be ascertained. These efforts were largely unsuccessful until I discovered a "pocket" of three rocker beater looms (loom #13, loom #14, and loom #15) within the Blue Ridge Mountain Parkway system of Virginia. Inquiring after these looms led to additional sources of information, and eventually to: 1) an additional number of looms, 2) a theory that southwestern Virginia may have been the point of origin of this style of loom, and 3) a search for early loom patents that might provide after-the-fact documentation of the style and confirm the Virginia point-of-origin theory.

The U.S. Patent Office first began issuing patents in 1790. According to early index records, three loom patents were issued between 1812-1814 to two inventers in the southwestern area of Virginia. Unfortunately, the original models and drawings were not available, having perished in the 1836 U.S. Patent Office fire. The following year the U.S. Congress made funds available and an attempt was made to reconstruct the early records by having patents resubmitted. The National Archives was able to provide numbers for the patents I desired: x1816, x2065, and x2117. An extensive search was conducted but no trace of these particular patents could be found, leading to the conclusion that they had not been resubmitted. It was suggested that my only recourse was to search for duplicate copies, which might have been retained locally by the inventors.

As my academic deadline approached (June 1998), the influx of information greatly increased, fostering new theories and making revisions unavoidable. I was advised to minimize revisions and limit the loom analysis to the first 20 loom found. However, when information and pictures were received concerning rocker beater loom #24, with legs loosely pinned to the side of the loom, I could not ignore it. The discovery of this loom, along with the drawing of Almond's loom and the Smith Family loom (an old pinned beater loom housed in the same museum as one of the rocker beaters), gave rise to two theories: 1) that Almond's loom may have inspired not one, but two Appalachian handloom styles - the rocker beater loom and also the "little rocking" (or pinned beater) loom, and 2) that in all probability, the loom with pinned legs came first with rockers being added as a later development.

I then asked William Ralph, a retired engineer and specialist in antique textile tools, "but why add the rockers at all?" He contemplated the question from an engineering standpoint and the following theory immerged - the outside curve on the rocker would provide a shifting pivot point for the relatively short beater leg, and thereby improve the parallel motion of the beater reed. With cane reeds and manual brake systems this motion would be especially advantageous to the weaver, being more gentle on the warp and allowing a longer portion of weaving to be done between advancements of the warp. Ohio University professor of Mechanical Engineering, Kenneth Halliday, generated a computer simulation to test the theory. Characteristics for both pinned and rocker legs were entered into the computer and a graph was generated for each. The figures were set in motion and the positions of the numbered points (at the upper ends of the legs where the reed would be) were charted. The resulting lines showed considerable osculation from point 12 (the pinned beater) but almost none from point 20 (the rocker beater) - proving the parallel motion theory correct.

Other theories would not be as easy to prove, and my thesis concluded with a number of recommendations for further study:

1) Continue the search for origin of rocker beater

2) Increase style awareness of the rocker beater feature through channels of publication and presentation

3) Continue the search for looms (and family histories) and document findings

4) Conduct "on site" research at known and probable locations in southwestern Virginia

5) Expand the patent search for early loom inventions in southwestern Virginia

6) Investigate possible links between John Almond's loom and the two Appalachian standing beater loom styles -- pinned and rocker.

Since publication of the thesis in 1998, I have devoted a significant amount of time and travel to address the above recommendations. In an effort to increase style awareness I have: 1) placed a copy of the thesis with each known loom, 2) developed an educational brochure for distribution in museums housing rocker beater looms, 3) written numerous articles for weaving and historical publications, 4) given public presentations to various weaving guilds and historical societies, and 5) developed this educational on-line website. As a result of these efforts, the number of known looms has more than tripled since the original study. I continue to document and photograph looms as they are located, and assemble background histories for those that have remained within their original families.

With reference to on-site research in southwestern Virginia. For a number of years I spent several weeks each fall in the southwestern cluster of counties known to have produced either rocker beater looms or early loom patents. I found additional rocker beater looms in the immediate area, and several old pinned beater looms. I gathered information on early textile production in the area, and information on John Heavin and John Sprinkle -- the two men from the area who submitted early loom patents -- but I was unsuccessful in finding local copies of the models and drawings that perished in the U.S. Patent Office Fire.

John Heavin, the man who submitted two of the three early loom patents, was born and raised in Montgomery County, Virginia. He was the prosperous owner of Lovely Mount Tavern, a wayside inn on the Wilderness Road, about a mile east of Ingles Ferry. Between 1806 and 1817 he patented eight inventions -- including the two looms (one in 1812, and the other in 1814). In 1827 the family left Virginia and migrated to Indiana. They were easy to trace because the immediate descendants played a significant role in the early development of central Indiana area. One of John's granddaughters married Reuben Ragan, Indiana's first horticulturist. Another granddaughter married Abram Ridpath, and produced two of the state's early historians: Gillum Ridpath, the first official historian of Putnam County, and John Clark Ridpath, who was instrumental in the development of DePauw University and became well known for his History of the United States, Prepared Especially for Schools. A statement from an article by John Clark Ridpath in an early Greencastle newspaper was of great interest to me. It concerned the family's move from Virginia, and read "... Into the big wagons the Heavins put everything they thought absolutely essential. Including a loom and parts for a new sawmill and a new gristmill, which he (John) planned to build. These inventions which remained in his family for generations were a great source of pride to his descendants." I traveled to central Indiana in hopes that John's descendants might be traced and his loom, or loom patents, found. I was able to locate the original Ragan homestead, and several Heavin descendants, but was unable to discover any sign of the loom or loom patents.

My hope of finding patent information was briefly revived, in 2004, by an article in the New York Times (August 9, pg. C2). The article stated that prior to the fire of 1836, patents were referred to by name and issue date only, and it was only after the fire that the Patent Office began assigning patent numbers. The article continued " As the patents lost in the fire were restored, they also were assigned sequential numbers starting with 1, and an "x" was added to distinguish them from the post-1836 patents." According to this article the patents I sought should have been in the archives along with the other restored patents -- since the National Archives had been able to provide me with patent numbers (x1816, x2065, and x2117). Regrettably, the article proved to be incorrect. I talked with Jim Davie, the Patent Office history expert quoted in the article. He said he had been misquoted, and that the X-Patent Index had been generated by combining several existing versions together. He assured me the sequential numbers had been assigned according to the original patent issue dates -- not the resubmission dates. He suggested I peruse local county court records, since inventors sometimes registered their patents at the local courthouse; other than that, my only other recourse would be to locate one of the patent looms. I did make a second search of the Montgomery County, Virginia, courthouse records and found several references to John Heavin, but none in connection with loom patents. The search for patents was eventually suspended after the second search for duplicate local copies proved unsuccessful.

Nevertheless, what I have learned from the research leads me to think the rocker beater loom style was fairly well established in Southwestern Virginia by 1794, almost 20 years prior to 1812 (the date of Heavin's first loom patent). Even if the missing patents are eventually located, and found to document the rocker beater, it would not prove that he was the original inventor. It would only prove he had made changes to the product and was familiar with the patenting process. In all likelihood, the origin of the rocker beater will continue to be a mystery, but patent information would help fill in certain parts of the overall puzzle.

I have yet to make any serious efforts in establishing a link between the two Appalachian standing beater styles (pinned and rocker). I have, however, received numerous requests for information from owners of old pinned beater looms, and have begun collecting interesting pinned beater loom pictures. These photographs can be can be viewed by going to either the Location of Looms page, or the far right column of the Loom Picture Album Index.

The link between John Almond's loom and the Appalachian standing beater loom styles is a matter of supposition. Prior to this study the prevailing theory of the standing beater was that it had been developed as a part of the power loom technologies of the Industrial Revolution. This prompted me to investigate those technologies in light of the date John Lamb migrated to Kentucky (1794). The first patent on a power loom with a standing beater was issued in Great Britain to Edmond Cartwright, in 1787. That date, along with the lack of resemblance between Cartwright's power loom and the rocker beater loom, made it seem an unlikely, if not impossible, source of inspiration. On the other hand, both the appearance and the date of John Almond's loom made it seem worthy of further research.

In 1771 John Almond, a British weaver from the village of Great Easton, Leicestershire, exhibited a handloom to a committee of England's Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce and received an award of 50 guineas. The society, now known as the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce (RSA), was founded in 1754 as a public service organization, primarily to stimulate developments that served the public good. Premiums were offered to encourage inventions that would increase textile production, because the job opportunities created would benefit the working classes. John Almond's design was a radical departure from the hanging beater loom of his day, and is thought to be the first use of an inverted (standing) beater. According to RSA records, Almond left his loom with the society "for the use of the public together with the web, shuttles, and everything now used in and belonging to the working of it." This statement originally led me to believe the design may have then been put into production and distributed by the society; however, the current RSA archivist, Nicola Allen, assured me that production and distribution of inventions would have been the responsibility of the inventor.

In July, 2005, I traveled to the United Kingdom, to learn more about John Almond, and to explore possibilities that he (or someone with knowledge of his loom) may have relocated to America or to Glasgow, Scotland, where in 1806 a man by the name of John Austin was residing when the RSA awarded him a gold medal for harnessing three hundred "Almond-type" looms to a power source.

I found Great Easton to be a small, picturesque, Leicestershire village. Many of its stone cottages date back hundreds of years, and immaculate thatched roofs add to the character. The land on which the town stands had been donated to the Abbot of Peterborough, around 700 A.D., who in turn leased it to Rockingham Castle for a fixed rent. Villagers could own land and houses through 'copyhold' -- an ancient and complicated arrangement with the Baron. Members of the Great Easton History Society helped me gather information during the course of my week there. Pictured here are those directly responsible for most of what I learned: Ena Meechan, Anne Wallis, Jean Crathorne, myself, and Jean Rands (whose great-aunt was an Almond). Anne Wallis and Ena Meechan were recently occupied with two BBC "Time-Team Digs" -- a long-running British TV series featuring archaeological digs in various UK locations. And to Ms Meechan, who was in the process of computerizing village historical records and stopped to create a comprehensive family tree plotting the Almonds of Great Easton -- beginning with Richard Almond (baptized in 1600) and ending with Jean Rands' great-aunt, Harriet Ann Clark Almond (buried in 1936) -- many thanks!

John Almond was born into a textile-producing family. His grandfather, Leonard, was a wool-comber by trade; his father, also named Leonard, was a weaver; and John was listed as a weaver as well. No local records indicate he was an inventor -- that is a fact known only through the RSA records. According to Parish records John's particular branch of the Almond family appears to have died out when he was buried in 1823, at 82. His grandfather, Leonard the elder, died at 36 in 1729, leaving Leonard the younger (age 10) and two small daughters. Leonard the younger lived to the age of 80, and had two sons, John and Charles. Charles was buried at the age of 20, on December 16, 1770, less than a month prior to John's being given the RSA award (January 8, 1771). According to local records, John and his parents lived in the Little London section of Great Easton. There is no evidence he ever married, relocated, or put his loom design into production. The home his family is thought to have shared is pictured here. In 1771, Great Easton was a self-sufficient village and everything needed for living was produced locally. Out-of-town travel was not uncommon, though many did not venture as far as London. John's trip to London may have been been his first, and the 50-guineas he received as prize money would have been equivalent to a full year's wages. With no male heirs to carry on his branch of the Almond family name/history/business, and no close male relatives who might have been traced to America, it is unlikely the link between John's loom and the Appalachian standing beater loom styles will ever be confirmed. Without such evidence, the British connection will continue to remain a supposition.

I also spent a week in Glasgow Scotland, conversing with the West of Scotland Guild of Weavers, Spinners, and Dyers and seeking information on John Austin. RSA records contain no drawings of the "Almond-type" looms Austin harnessed to power, but they do include references to buildings constructed at a Mr. J. Monteith's spinning-works, for the purpose of housing his looms (the first contained 30 looms and the second about 200). It also mentions the model submitted for RSA inspection had been improved so that "from 300 to 400 of these looms may be worked by one water-wheel or steam-engine, all of which will weave cloth, superior to what is done in the common way." In Glasgow I found several local references to Mr. Montheith's business, and the Muirs (my Scottish hosts/tour guides) took me to see the long-abandoned spinning-works site. I was unable to find any local drawings of the looms; I did, however, find a notice that John Austin died November 26, 1806, just eight months after receiving his RSA award.

When my final efforts to locate patents x1816, x2065, and x2117 were unsuccessful, and Patent Office history specialist Jim Davie implied my only recourse was to locate one of the actual patented looms, I had no expectations that this would actually happen. Then on July 4, 2011, I received a phone call followed by cell phone photographs of an old mechanical fly shuttle loom unearthed in an abandon 19th century weaver's shop in Draper Pennsylvania. The caller was part of a community effort to clean up the eyesore and, thinking a museum might be interested in the contents, found my website by doing an on-line search for museum loom images. How he was able to distinguish any resemblance, between the hand made rocker beater looms on my site and the pile of machinery parts he was photographing, is quite amazing, as it took me some time to see it myself.

The photographs arrived over a period of several days (to see additional photographs click here), with those showing clearer details of the rocker being closer to the end. I forwarded the photographs on to my patent loom consultant who confirmed they were, indeed, that of a patented fly shuttle loom with the rare rocker beater component, and it was obviously more than a century old. She agreed the loom was museum-worthy, and felt an appropriate location could be found. When queried about patent references the caller said he could find no parts with numbers stamped on them, other than the 1895 date, and no patent references in the accompanying paperwork. According to the patent loom consultant, it is possible to conduct a patent search beginning with the object in question, but it is a difficult and time-consuming task and could take years to accomplish. I plan to eventually undertake this project, but only time will tell if it can be accomplished. It is satisfying; in the meantime, simply to have proof that at one point the rocker beater was considered cutting-edge technology worthy of being patented. Hopefully in the near future, this loom can be assembled and placed in a new location, and photographs will be available for the website.

2013 Update on Fly Shuttle Loom Find

Unfortunately, the loom's official paperwork (bill-of-sale, parts list, owner's manual, etcetera) has disintegrated, or been lost, which is certain to complicate attempts to acquire manufacturing and patent information; and brings an added challenge to restoration efforts. Therefore, when I approached Pat Hilts, curator of the Home Textile Tool Museum in Orwell PA, about the possibility of placing the loom in that facility, I was elated when she agreed to meet in Draper to see the loom and assess our chances of successfully restoring it. We met there in August and, with community help, began sorting through the pile of junk to separate out the identifiable loom parts. After several false starts, and a considerable amount of experimentation, we were delighted with our trial effort to assemble the loom (see below), and reasonably certain none of the major parts were missing.

While there, we learned more about the community members helping us with the project. All were members of the same extended family, and the family patriarch had actually known the weaver, Frank Ogden, and worked in the shop as a child. He was unable to tell us much about the loom itself, other than it had been one of two looms in the shop, and was not the one he had used. He remembers most of the neighborhood boys working in the shop from to time - doing all kinds of chores, including weaving - and Ogden being not just a master weaver, but also an expert mechanic and community leader.

In

the fall, after the Home Textile Tool Museum closed for the season, the

loom was transported to Orwell, and reassembled.

Plans are

to have a partial exhibit ready when the museum reopens for the

2014 season; however, total

restoration of the loom is likely to take a while

to complete. For additional museum information see:

http://www.hometextiletoolmuseum.org.

Professional Fly Shuttle Rocker Beater Loom Exhibit - 2014

When the Home Textile Tool Museum reopened Memorial Day weekend the loom restoration process was still in the infancy stage; therefore, the exhibit: Handweaving at the Beginning of the 20th Century: Frank K. Ogden of Draper PA and his Rocker Beater Loom, opened as a "work in progress." A set of professional poster boards conveyed pertinent information regarding Frank Ogden and his weaving shop (click here for Frank Ogden page), while another provided general information on the rocker beater loom style and research. The exhibit was allotted a pride-of-place position in the Thrashing Barn, with plenty space for restoration activities.

Beneath 100-plus years of dust and soil the basic wooden loom-frame was in excellent condition, and while the metal parts had varying degrees of rust, the overall clean-up job was relatively easy. On the other hand, the loom's various mechanical systems present a different story. They are complex in nature and seem to have been more adversely affected by the years of wear and neglect. Adding to the difficulties has been the absence of any sort of instruction book or owner's manual, thereby necessitating lots of guesswork and the use of various trial-and-error techniques in the effort to return the loom to working order.

The counterbalanced shedding system, is relatively simple. It consists of two heddle frames complete with heddles (visible within castle, in photo above right), two foot-treadles, and a central pivot beam linking the system together by means of leather straps and metal connecting rods. It took a bit of sorting out to get the system operational, but after replacing the leather straps, repositioning the metal rods, and making a few other adjustments (above left), the shedding system is now working.

The beating-up system itself is relatively simple. It consists of beater frame with handrail and reed (visible in photo at right), and offset rockers attached below. The beater is operated manually and works smoothly. However, the accompanying fly shuttle system, with paraphernalia attached to both castle and beater frame, does not work smoothly at this point. The shuttle action is triggered by rising heddle frames during the shed-changing process, and components related to that action are affixed to the castle: toggle switches, one at each end of the castle, a single (badly damaged) strike block unit attached at the midpoint, and guide wires connecting the elements. The remaining components of the fly shuttle system are either attached to, or embedded within, the beater frame: strike levers (visible here just below the strike block) are actually upward extensions of cast-iron rods lodged within the beater frame; the rod's downward extensions are secured to trigger sticks, connected by straps and pulleys to picker sticks that ultimately shoot the shuttle back and forth between shuttle boxes located at opposite ends of the beater frame. The mechanics of the fly shuttle system work as follows: Step 1) the weaver steps on one of the foot treadles - this action changes the shed, trips one of the toggle switches, and causes the strike-block to shift positions; Step 2) the weaver then grasps the handrail and firmly pushes the beater toward the castle, causing a chain reaction - one of the cast-iron levers hits the strike-block and is forced toward the front of the loom while the trigger stick at the opposite end of the rod is forced to the rear of the loom, this forces the strap to jerk the picker stick toward the loom and sends the shuttle flying toward the opposite side of the loom, with a pick of weft left in its wake; 3) the weaver then completes the action by drawing the beater forward to beat the weft into the web. To send the shuttle back across the loom, the weaver need only step on the opposite foot treadle, to restart the cycle and continue the weaving process.

While we were successful in getting the shuttle to shoot from one side of the loom to the other, the action was unpredictable and (more often than not) the shuttle had to be retrieved from distant parts of the barn. To be sure of having a token weaving on the loom in time to introduce the exhibit, we reverted back to hand-thrown shuttles.

The warp-tensioning system consists of the cloth beam brake (pawl & ratchet and brake release lever & pawl), the warp beam brake (pawl & ratchet and a brake lever & pawl), and the warp beam brake release mechanism, which is attached to a trip-wire that extends the full length of the loom. There are numerous problems concerning the braking system. The easiest to fix - straightening the bent trip-wire - has been accomplished (above left). The more difficult problems have yet to be solved. Both pawl and ratchet sets are made of cast-iron, and neither is user-friendly - with the brake release mechanisms being especially difficult to operate. Hopefully, dealing with the rust will help. Additional problems include: 1) the complexity of the system, 2) the fragile condition of the release mechanism, and last but not least 3) one of the warp beam brake parts is missing - the part is thought to extend from the warp beam brake lever to the front of the loom. The missing part is represented by a long narrow board in the top-most (side-view) photo in this section, but is likely to be shorter in length.

The loom restoration project is well underway, and the work will continue. However, the research has come to a standstill until we can learn the identity of the manufacturing company that produced the loom. We know at least one additional loom of this type exists - as there were originally two in Ogden's weaving shop - the same except for size. We suspected this when we found one of the loom beams to be two inches too short - note arrow in photo (above right) pinpointing the gap between the beam tenon and the loom-frame mortise. We spoke to Ogden's grandson, and he confirmed the two looms were identical except one was slightly larger than the other. At some point following Ogden's death, in 1948, an antique dealer managed to acquire the smaller loom. The whereabouts of that loom is unknown - except for the single beam that was left behind. Without the stabilizing beam the front loom posts tend to splay apart at the bottom, so the short beam has now been extended and properly inserted.

For labeled shetches, and a list of the loom's systems and individual components, go to Fly Shuttle Rocker Beater Loom #1.

The search for information on the manufacturer of this loom remains an on-going project, and anyone with knowledge of additional fly-shuttle rocker-beater looms, or pertinent information on the subject, is requested to contact the author at phyllis.d.dean@gmail.com, or by phone: 740-593-8487 (home) or 740-591-1591 (mobile).

|

Links To Other Web Site Sections: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|