|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

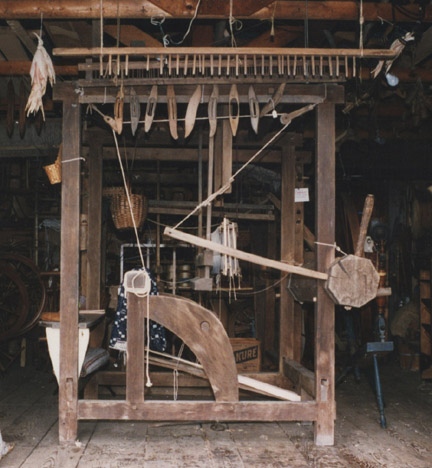

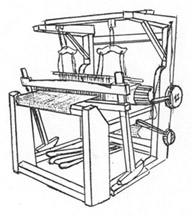

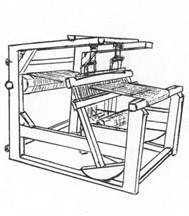

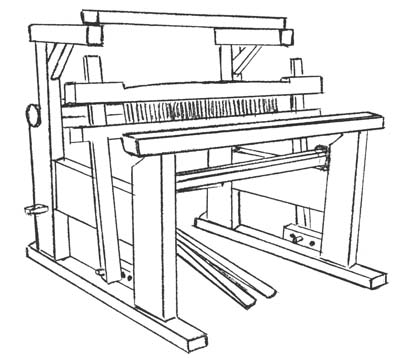

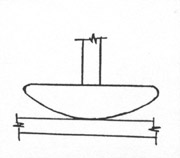

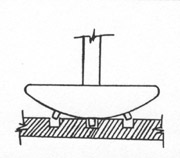

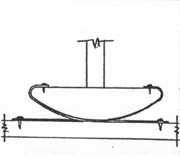

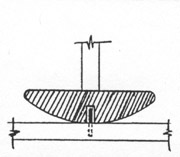

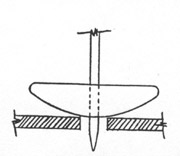

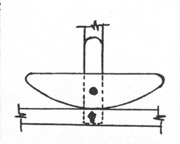

In the decades following the American Revolution, a radical new loom style began appearing on the western frontier. What set this loom apart was its beater (the apparatus that beats the thread into cloth). Rather than hanging from the loom frame in the typical overhead position, this beater operated from a standing position, and it was supported by a set of wooden rockers (not unlike those on an infant cradle or a rocking chair) that rested on the base of the loom and facilitated the beating action.

Side view of beater hanging down from center Side veiw of beater, note rocker at lower left

Around 60 of these rare looms with rockers are known to exist - a few remain within their original families but most are now in museums or private collections. Little documented history is available on the handmade looms of this period, since they were usually built by a relative or neighbor and came with no bill-of-sale or identifying trademark. Information must be obtained from oral and written family histories and from legal records attesting to the occupations and skills of the builders.

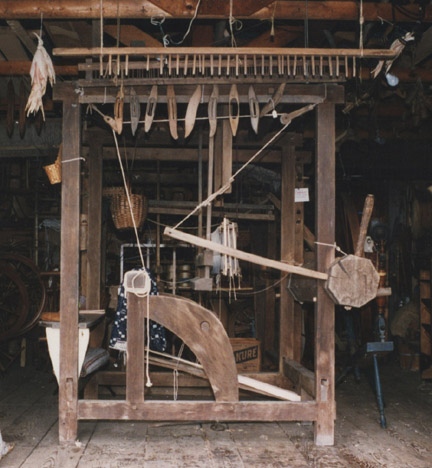

One family of weavers, the Lamb family of Kentucky, can account for two rocker beater looms build by their ancestors. The older loom is attributed to John Lamb (1760-1842), patriarch of the family. John Lamb had been an apprentice weaver in Salisbury, North Carolina, at the time of the American Revolution. He joined in the fight for independence, like all able-bodied young men of the time. Years later (1794) took his growing family and migrated to western Kentucky. He resided there until 1816, when most of the family moved on across the Ohio River into what is now southern Illinois. Only his eldest son, James, and his family, remained behind and retained the Kentucky land holdings. Left behind in the original log cabin, was a rocker beater loom that John had constructed during his sojourn in the state. The loom remained within the James Lamb family until the 1950s when it was donated to the Bob Wheeler Museum in Marion Kentucky.

John Lamb's Loom (right front view of loom) Harvey Lamb's Loom (left rear view of loom)

Following the Civil War, a second loom was built by Harvey Lamb, a son of James. Harvey was a cabinetmaker by trade and he built the loom at the request of his niece, Sarah Lamb, using his grandfather's old loom as a pattern. This loom, too, remained within the Lamb family.

In 1994 Phyllis Dean acquired her great-grandmother Sarah Lamb's loom, and learned of the older Lamb loom as well. When she could find no picture or mention of the unique style in loom literature, she traveled to North Carolina hoping to find additional looms and/or information. Finding neither, she began contacting museums, loom authorities, and weaving guilds in the United States and abroad. What she eventually learned from this extensive search led her to believe that John Lamb had seen the style in the Appalachian Mountains of southwestern Virginia, as he and his family migrated through the area on their way west to Kentucky.

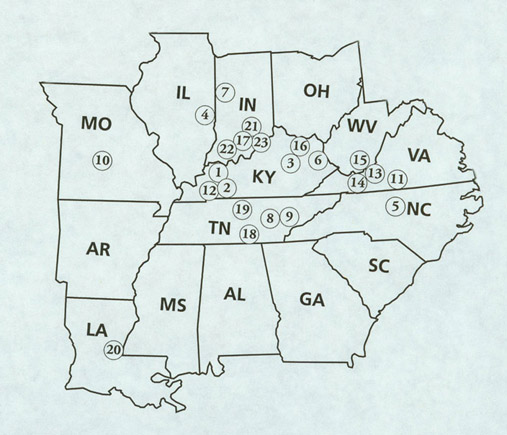

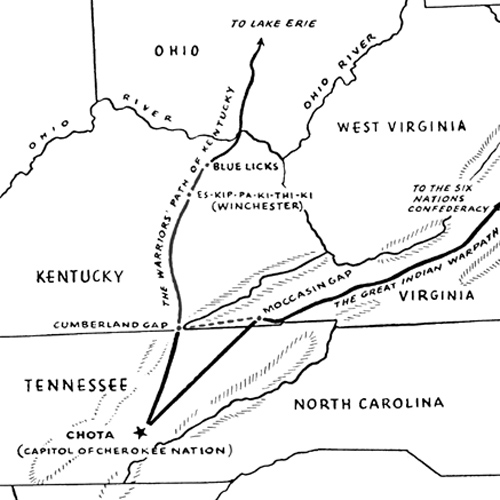

The map above depicts the reported locations of the rocker beater looms in the original study, and pinpoints an important area in southwestern Virginia. From there, locations fan out to the northwest, west, and southwest, appearing to coincide with the post-revolutionary pattern of western migration.

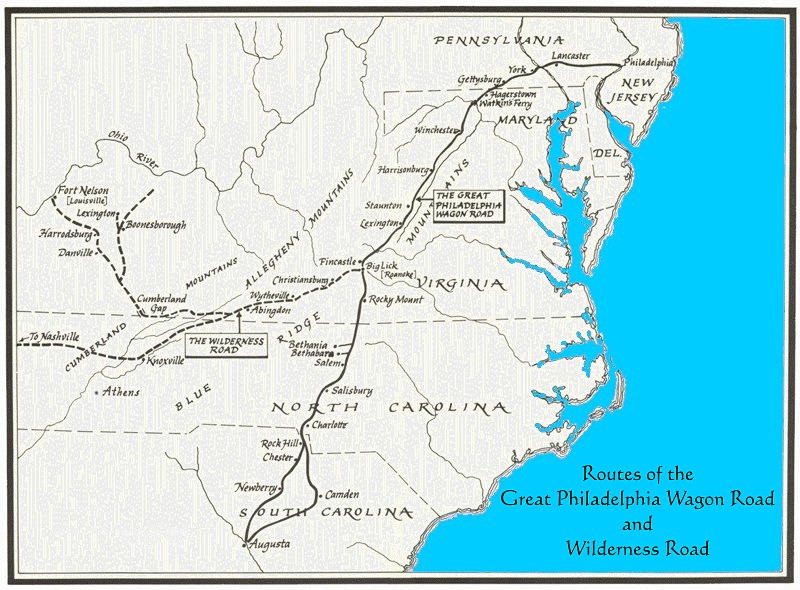

A natural roadway known as The Great Indian Warpath crossed the region. In 1744 the Indians relinquished rights to the trail, and the north/south corridor became the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road.

At Big Lick (Roanoke) the trail split, and the western branch became known as the Wilderness Road. In 1775 Daniel Boon and his crew of road cutters extended the Wilderness Road through the mountainous area to Cumberland Gap (indicated on map below by dashes). It was not the only way west, but it provided the easiest way through the Appalachian mountains. The road was widened from a pack trail to a turnpike (a wagon road with tollgates) in 1797 but, even prior to that, an estimated 70,000 people had taken Wilderness Road through the gap.

Loom owners whose looms have remained within their original families are found to have several things in common. The most significant being that their ancestors either lived in this "Wilderness Road" section of Virginia, or migrated through the area, and were among the earliest settlers in their respective areas as new states and territories were opened to settlement in the late 1700s/early 1800s.

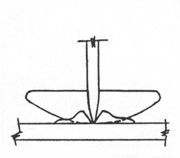

Rocker beater looms don't all look alike. A few look like the old hanging beater looms that were common on the western frontier; in fact, on several looms the old fashion hanging beater was simply removed and replaced with the new, upside-down beater. But most of the rocker beater looms have a modern appearance, or at least a more compact look than the old-style looms (click on bold underlined captions to see actual looms).

Old

Style Rocker Beater Loom

New

Style Rocker Beater Loom

Mixed

Style Rocker Beater Loom

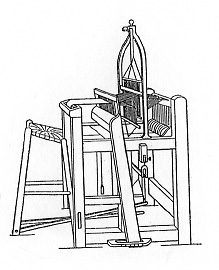

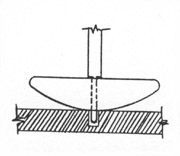

The standing beater and the modern appearance are normally associated with power looms of the industrial revolution; therefore, many assume that rocker beater looms could not be as old as they are reported to be. There is undisputed evidence, however, that at least one handloom with a standing beater existed years before the first power loom was invented. In 1771 British inventor John Almond won a Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce (RSA London) award for the loom pictured below. His loom is important because it is the earliest known standing beater loom, and its modern appearance is quite similar to several of the new-style rocker beater looms. One major difference is that, instead of having rockers, the legs of Almond's beater were simply pinned to the loom frame. Interestingly, there are many old standing beater looms in Appalachia that have legs pinned to the frame (see below) - more than there are with rockers.

John

Almond's Loom

Pinned

Beater Loom

There are many questions concerning these looms. Was Mr. Almond's loom the inspiration for one, or both, of the Appalachian standing beater loom styles? If so, who brought the idea to America, and who added the rockers?

The rocker is the single defining element for this particular loom style. The rockers provide a pivot arrangement similar to that of the hanging beater, in that it gives the beater a natural point of balance to return to when at rest; in addition, the outside curve of the rocker affects a shifting pivot point which allows improved parallel motion of the reed from a relatively short beater leg (for explanation see "Last Minute Research" in the research section).

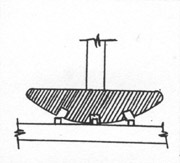

There is considerable difference in the rockers on the various looms, and also in how they are kept in place on the base of the looms. In photographs it is often difficult to see how the rockers are attached; the sketches below are able to show details more clearly (click on bold underlined captions to see representative looms).

Several looms have "free-standing" rockers but on the rest, rockers are kept in place by a variety of ingenious methods. Most common is the "peg and hole" method. Some looms have pegs on the underside of the rocker, and corresponding holes in the base of the loom, while others have the opposite configuration.

The next most common method is with "rocker straps." The straps can be made of wood, metal, leather, or canvas. When wooden straps are used, they consist of one (usually) very thin, somewhat flexible, narrow, strip lying along the length of the rocker, one end is secured to the end of the rocker and the opposite end is secured to the loom base. When other strap materials are used, two straps are needed for each rocker. The straps lie side by side along the length of the rocker, one end of each strap is secured to a rocker tip (one strap to the front tip and the other strap to the back tip) and the opposite end of each strap is secured to the loom base.

Rocker

Straps

Hole &

spike

Pointed leg

& receptacle

The rest of the looms have one-of-a-kind methods of keeping rockers in place: 1) "hole & spike, 2) "pointed leg & V-receptacle," 3) "extended projection and hole," 4) "dagger & special platform," and 5) "pinned leg and rocker." In the last mentioned case, the lower end of each leg is loosely pinned to the base of the loom, but the rocker retains control of the beater action.

Extended

projection & hole

Dagger &

special platform

Pinned leg

& rocker

To see individual photographs rather than drawings, click on each underlined caption. For additional information on the research go to Original or Continuing Research sections.

|

Links To Other Web Site Sections: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|